Karl Marx’s Capital: A Critique of Political Economy stands as one of the most influential and incisive analyses of capitalism ever written. Composed over decades and published in three volumes (with two edited posthumously by Friedrich Engels), the work dismantles the economic, social, and philosophical foundations of capitalist society. Marx’s aim was not merely to critique classical political economists like Adam Smith and David Ricardo but to expose capitalism’s inherent contradictions, its exploitative mechanisms, and its historical trajectory toward crisis and transformation.

Three Volumes

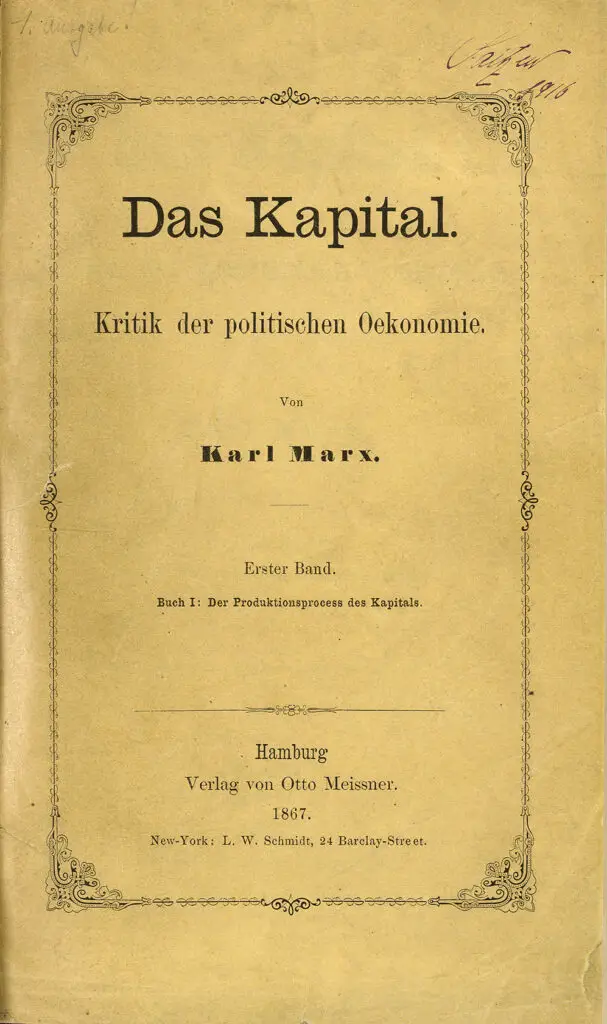

- Volume I: The Process of Production of Capital (1867)

Marx begins with the basic unit of capitalism: the commodity. He develops the labor theory of value, arguing that a commodity’s value derives from the socially necessary labor time required to produce it. This volume introduces surplus value—the profit extracted from workers’ unpaid labor—as the engine of capitalist accumulation. Marx also unveils commodity fetishism, the illusion that market relations between objects (e.g., prices) are natural, masking the underlying exploitation of human labor. The brutal realities of factory labor, mechanization, and the growing divide between capitalists (bourgeoisie) and workers (proletariat) underscore his analysis. - Volume II: The Process of Circulation of Capital (1885)

Here, Marx shifts focus to how capital moves through cycles of production, exchange, and reinvestment. He examines the roles of money capital, productive capital, and commodity capital, dissecting the reproduction of capital on both simple and expanded scales. Key themes include the turnover time of capital, the distinction between fixed and circulating capital, and the potential for crises arising from mismatches in production (e.g., overproduction) and circulation (e.g., unsold goods). Volume II lays groundwork for understanding capitalism’s systemic instability. - Volume III: The Process of Capitalist Production as a Whole (1894)

The final volume synthesizes Marx’s critique, addressing capitalism’s “big picture” contradictions. He explores how competition among capitalists drives the tendency of the rate of profit to fall—a result of rising investment in machinery (constant capital) over labor (variable capital), the sole source of surplus value. Marx also analyzes how surplus value is redistributed as profit, interest, and rent, critiquing the roles of bankers, landlords, and merchants. His discussion of fictitious capital (e.g., stocks, bonds) and credit systems foreshadows modern financial crises, arguing that capitalism’s speculative tendencies exacerbate inequality and instability.

Methodology and Legacy

Marx employs a dialectical materialist framework, tracing how contradictions within capitalism (e.g., between socialized production and private ownership) generate crises and class conflict. His goal is both scientific and revolutionary: to reveal capitalism’s laws of motion while empowering the proletariat to overthrow it.

Though unfinished, Capital reshaped global politics, economics, and philosophy. It inspired revolutions, labor movements, and critical theories while remaining a touchstone for debates about inequality, exploitation, and alternatives to capitalism. Critics challenge its labor theory of value and historical predictions, yet its insights into commodification, alienation, and systemic crisis remain eerily relevant in an age of globalization and financial speculation.