Bronisław Malinowski’s Argonauts of the Western Pacific is a landmark in anthropology, offering a vivid account of the Trobriand Islanders of Papua New Guinea. Published in 1922, this work serves as a foundational text for modern ethnographic studies, emphasizing participant observation and meticulous fieldwork. The book broke new ground in the discipline by moving beyond armchair anthropology, which had relied heavily on secondhand accounts and unverified narratives. Instead, Malinowski immersed himself in the culture he studied, living among the Trobriand Islanders for several years. This innovative approach allowed him to document their lives in unprecedented detail, capturing the nuances of their social systems, rituals, and daily practices.

At its core, Argonauts of the Western Pacific examines the Kula exchange, a complex system of ceremonial trade involving the exchange of shell valuables across a network of islands. While the book’s focus is ostensibly on this economic practice, its scope extends far beyond. Malinowski uses the Kula as a lens through which to explore the broader social, cultural, and psychological dimensions of Trobriand life. He articulates the ways in which this exchange system binds together isolated communities, reinforcing alliances and social hierarchies. His analysis challenged earlier anthropological assumptions about “primitive economies” by demonstrating their sophistication and integration into complex social and symbolic systems.

B. Malinowski coined the term functionalism. While studying the Australian aboriginal tribes of the Western Pacific islands he concluded that it was possible to link up functionally the various types of cultural response such as economic, legal, scientific, magical and religious to human physiological needs.

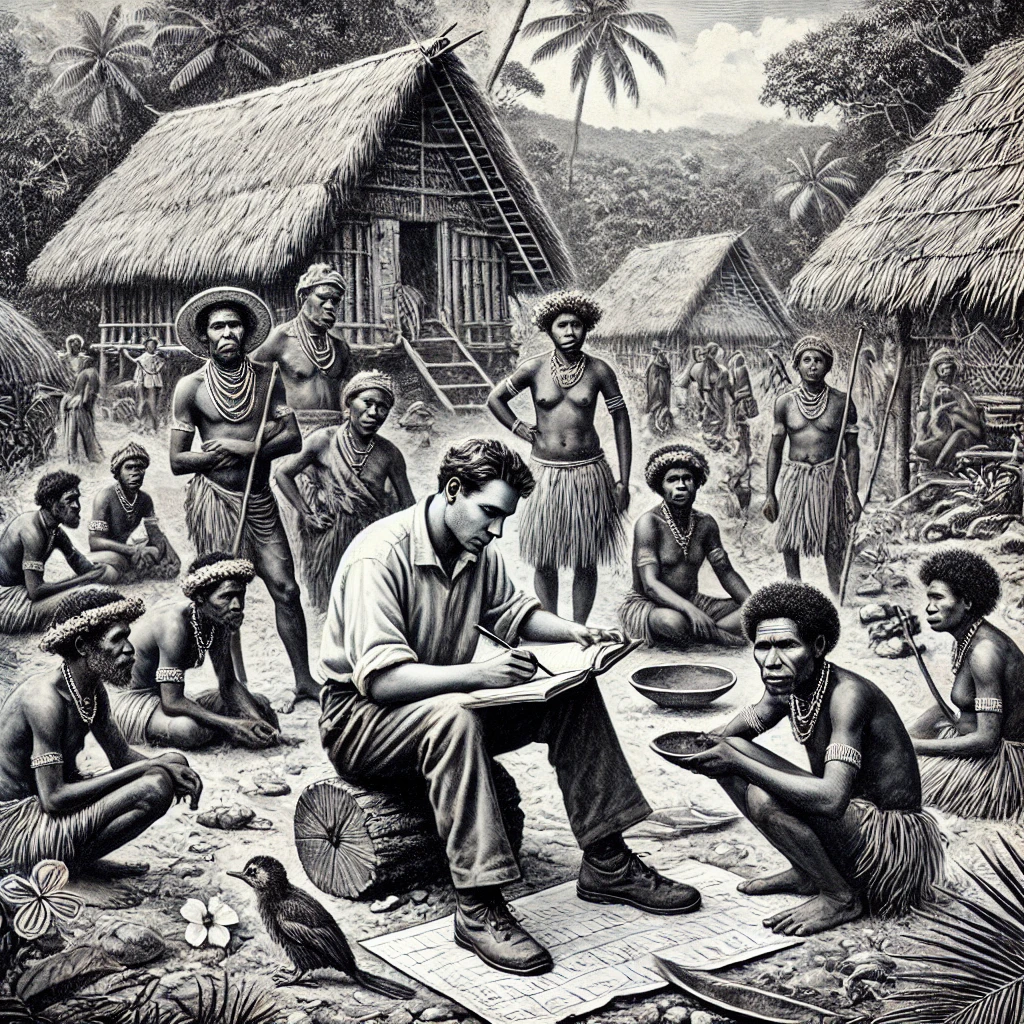

Malinowski’s emphasis on the “native’s point of view” was a methodological breakthrough. He sought not just to describe Trobriand customs but to understand how the islanders themselves perceived and made sense of their world. This approach, which he termed “participant observation,” required the ethnographer to engage deeply with the community, learning their language, participating in their rituals, and observing their routines over extended periods. By doing so, Malinowski argued, the anthropologist could grasp the “imponderabilia of everyday life”—the small, often overlooked details that provide crucial insights into a society’s structure and values.

The publication of Argonauts of the Western Pacific marked a turning point in anthropology, setting a new standard for ethnographic research and writing. The book’s detailed narrative style, combined with its theoretical rigor, made it accessible to both academic audiences and general readers. It offered not just an account of the Trobriand Islanders but a compelling argument for the importance of fieldwork in understanding human cultures. Today, Malinowski’s work remains a touchstone for anthropologists, celebrated for its depth, innovation, and enduring impact on the field.

Introduction to the Kula Ring

The Kula ring is not merely a system of barter or trade but a cultural institution deeply intertwined with the Trobriand Islanders’ social and spiritual lives. As Malinowski meticulously explains, this exchange is governed by strict rules and traditions that dictate not only what can be traded but also when, how, and with whom the exchanges take place. He vividly narrates the preparation for these voyages, describing how participants painstakingly construct and decorate their canoes. The process is ceremonial, with chants and rituals ensuring the protection of the voyagers and the success of their mission. Malinowski writes:

“The act of exchanging a mwali or soulava is not casual; it is fraught with obligation, expectation, and honor. A failure to participate or fulfill one’s role can have lasting social consequences.”

The symbolic nature of the Kula items is profound. Each mwali and soulava carries its own name, history, and legacy, often associated with prominent chiefs or legendary ancestors. This historical significance imbues the objects with what Malinowski calls a “biography,” transforming them into carriers of identity and prestige. For the Trobrianders, the Kula is a system that binds islands together, fostering cooperation and diplomacy amidst otherwise isolated communities.

Fieldwork and Methodology

Malinowski’s methodology broke from the armchair anthropology of his predecessors, which relied heavily on secondhand accounts. Instead, he lived among the Trobriand Islanders, engaging with them daily, participating in their activities, and observing their routines. His diary reveals the challenges of this immersive approach: the initial language barriers, the cultural misunderstandings, and the physical and emotional toll of fieldwork. “To be with the natives, to listen to their chatter, to see them in their natural environment — this alone can yield a true picture of their life and culture,” he asserts.

He narrates anecdotes of sharing meals with the islanders, joining them in their gardens, and even learning their songs and dances. This deep engagement allowed him to gather detailed accounts of their practices and beliefs, including the intricate protocols of the Kula ring. By speaking in the native language, he could uncover nuances that would have otherwise been lost in translation, capturing the essence of their worldview.

Malinowski’s insistence on recording what he called the “imponderabilia of everyday life” marked a significant methodological shift. He documented not just grand ceremonies but also the mundane details of canoe repairs, women weaving mats, and children playing. These small moments provided insights into the broader social fabric of Trobriand society.

Social Organization and Matrilineal Kinship

Trobriand society’s matrilineal system is both complex and foundational to its social structure. Property, rank, and clan membership pass through the mother’s line, placing the maternal uncle in a position of authority over his nephews and nieces. Malinowski describes this relationship with rich detail, noting how the uncle not only oversees his sister’s children but also serves as a mentor, disciplinarian, and benefactor.

He recounts a poignant moment when a young boy approached his uncle for support in preparing for a yam exchange, underscoring the uncle’s role in facilitating his nephew’s social ascent. Malinowski explains: “The maternal uncle embodies the intersection of obligation and affection, a figure both feared and revered.”

Fatherhood, by contrast, is a more informal and sentimental relationship. Fathers shower their children with affection and gifts but do not hold any formal authority. This distinction reveals how Trobriand society separates biological and social roles, reflecting their unique understanding of kinship and family. These relationships, Malinowski argues, are not only personal but deeply tied to the broader clan structure, with each individual’s identity rooted in their matrilineal lineage.

Gardening and Economic Activities

Gardening, particularly the cultivation of yams, occupies a central place in Trobriand life. Yams are more than food; they are symbols of wealth, masculinity, and social obligation. Malinowski describes the elaborate process of yam cultivation, from clearing the land to planting, tending, and harvesting. These activities are often accompanied by magical spells and rituals, believed to enhance the crop’s yield.

Malinowski narrates an episode where a man, eager to impress his in-laws, spent weeks crafting an intricate yam house to display his harvest. The man’s efforts were not just about showcasing his agricultural skill but also about fulfilling his obligations to his wife’s family. As Malinowski observed: “The yam house stands not only as a storage facility but as a monument to the gardener’s diligence and social connections.”

Yams are often exchanged in ceremonies, with their size and quantity reflecting the giver’s status and the strength of their social ties. These exchanges are competitive, with men vying to outdo one another in their contributions. The economic and symbolic dimensions of gardening, Malinowski notes, are deeply interwoven, revealing the Trobrianders’ intricate understanding of value and reciprocity.

Magic and Belief Systems

The Trobrianders’ belief in magic permeates all aspects of life, from agriculture to navigation. Malinowski recounts how spells are passed down through generations, often guarded jealously by those who know them. These spells are believed to invoke supernatural forces, ensuring success in endeavors that might otherwise fail. In one account, a group of sailors preparing for a Kula expedition performed an elaborate ritual involving chants, offerings, and the sprinkling of magical substances on their canoe. Malinowski noted the solemnity of the occasion:

“Each word of the chant is imbued with power, each gesture a key to unlocking the forces of the unseen world.“

The belief in sorcery also influences social dynamics. Accusations of witchcraft can disrupt relationships and fuel tensions within the community. Malinowski observed how such accusations often arose during periods of misfortune, serving as a way to explain and address crises.

The Role of Ceremonies and Feasts

Ceremonies and feasts are pivotal in Trobriand society, serving as stages for the display of wealth, status, and alliances. Malinowski describes these events in rich detail, noting the intricate preparations and the festive atmosphere. Feasts often coincide with significant milestones, such as the launch of a Kula expedition or the conclusion of a successful yam harvest.

At one feast, Malinowski witnessed a chief distributing enormous quantities of yams, pigs, and other goods to his followers. This act, he explains, was not mere generosity but a calculated display of power and leadership: “The feast is a theater where social roles are performed and reaffirmed, where alliances are forged, and hierarchies are reinforced.”

These events also serve as opportunities for storytelling, dance, and other forms of cultural expression, providing a window into the Trobrianders’ rich artistic traditions.

The Importance of the “Imponderabilia of Everyday Life”

The “imponderabilia” — the seemingly insignificant details of daily life — are a recurring theme in Malinowski’s work. He describes how these moments, such as a woman gossiping while weaving or a child practicing a chant, reveal the deeper rhythms of Trobriand culture.

For instance, he observed a group of boys playing a game that mimicked the Kula exchange, demonstrating how cultural norms and practices are passed down from one generation to the next. He reflects: “Even in their play, the children rehearse the roles they will one day assume, internalizing the values and expectations of their society.”

By documenting these details, Malinowski captures the texture of Trobriand life, offering insights that transcend the more formal aspects of their culture.

Contributions to Sociology and Anthropology

Malinowski’s work revolutionized anthropology, setting a new standard for ethnographic research. His insistence on long-term fieldwork, immersion in the culture, and the use of native languages paved the way for future anthropologists. He wrote: “The ethnographer must not only observe but also participate, living the life of the people he studies to understand the full scope of their culture.”

This approach, combined with his detailed analysis of the Kula and other practices, established him as a pioneer in the field, whose influence continues to shape anthropology today.

Critical Evaluation

While Argonauts of the Western Pacific is celebrated, it has also faced criticism. Some scholars argue that Malinowski’s portrayal of Trobriand society is overly functionalist, reducing cultural practices to their utilitarian purposes. Others have critiqued his position as an outsider interpreting a foreign culture. Despite these critiques, the work remains a cornerstone of anthropological literature, praised for its depth, clarity, and innovative approach.

Conclusion

Argonauts of the Western Pacific is more than an ethnographic study; it is a narrative that bridges cultures and challenges preconceived notions about human societies. Through detailed observations and empathetic analysis, Malinowski illuminates the complexities of the Trobriand Islanders’ lives, offering profound insights into the universal and particular aspects of human culture. As he concluded: “In the study of the Kula, we find not just a savage custom but a mirror reflecting the fundamental principles of human society.”

Bibliography

- Malinowski, B. (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An account of native enterprise and adventure in the archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea. London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. Retrieved from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/55822/55822-h/55822-h.htm

- eGyankosh. (n.d.). Malinowski and the Kula exchange. In Anthropological theories and concepts. Retrieved from https://egyankosh.ac.in/bitstream/123456789/83666/1/Block-2.pdf

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) OpenCourseWare. (2019). The anthropology of politics, persuasion, and power: Kula exchange in the Trobriands (Section 1, Module 2 Response). Retrieved from https://ocw.mit.edu/courses/21a-506-the-anthropology-of-politics-persuasion-and-power-spring-2019/4f526f56804fddcbe187530e859dad60_MIT21A_506S19_Sec1Mod2Respons2.pdf

- Young, M. W. (1972). The Kula: Social anthropology and ceremonial exchange. Annual Review of Anthropology, 1(1), 159-192. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.01.100172.001111

- Weiner, A. B. (1988). The Trobrianders of Papua New Guinea. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Leach, E. (2004). Malinowski’s contribution to fieldwork methods and functionalist theory. In Anthropology: Theoretical practice in culture and society. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Shore, B. (1982). The logic of Kula: Exploring the interplay of economics and symbolism in Trobriand society. Ethos, 10(2), 117-148. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.1982.10.2.02a00030