Introduction

Feminism is broadly understood as the advocacy of women’s rights on the basis of the equality of the sexes. It encompasses a range of socio-political movements, ideologies, and theoretical frameworks all united by the goal of ending women’s subordination to men and ensuring gender equality. Feminism critiques patriarchy – social systems in which men hold disproportionate power – and seeks to dismantle it through legal reform, cultural change, and social activism. Early feminist campaigns focused on basic civil and political rights, and over time this expanded to include economic justice, reproductive autonomy, cultural representation, and personal autonomy. Historically, feminist movements have been a driving force behind major social changes: for example, they achieved women’s suffrage, reproductive rights, and expanded educational and employment opportunities for women. In short, feminism is both a social justice movement and an intellectual project that asserts “women and men should have equal rights and opportunities,” challenging the deeply entrenched norms that grant privilege to one gender over another.

Historical Origins and Development of Feminism

Feminist thought and activism have deep historical roots, emerging in various forms long before the term “feminism” was coined. Early proto-feminist writers (15th–18th centuries) laid the groundwork for later movements by questioning traditional gender roles and arguing for women’s education and moral agency. For example, Christine de Pizan (1364–1430) was a late medieval scholar who defended women’s intelligence and capacity in works like The Book of the City of Ladies (1405). De Pizan refuted misogynist portrayals of women and “appealed for the education of women based on women’s inherent reason and the justice of gender equality”. Similarly, Mary Astell (1666–1731), often called the first English feminist, famously asked, “If all men are born Free, why are all women born slaves?”. Astell’s 1694 A Serious Proposal to the Ladies argued that women deserve the same intellectual training as men. These early feminists did not use the word “feminism,” but they articulated key ideas – equality, education, critique of male dominance – that would resurface in later waves.

First Wave (mid-19th – early 20th Century)

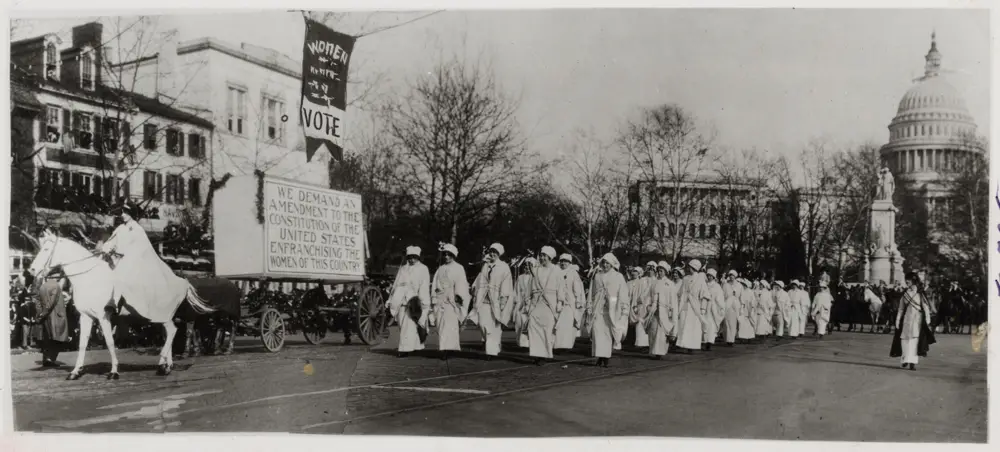

The first wave of feminism refers to 19th- and early 20th-century movements for legal and political equality, especially women’s suffrage. Intellectual precursors included Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), whose A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) argued that women possess the same natural rights and rational capacities as men. Wollstonecraft’s demand that women be educated to the same standards as men set the stage for feminist arguments to come. In the mid-1800s, suffrage activists in the United States such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott organized the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention, which produced a “Declaration of Sentiments” demanding women’s voting rights. Black abolitionist women like Sojourner Truth (1797–1883) combined gender and racial justice in speeches such as “Ain’t I a Woman?” (1851). In that speech Truth powerfully demonstrated women’s strength and capability by describing her experience performing labor traditionally reserved for men. Her oratory, in front of white and Black audiences, highlighted the intersecting oppressions of sexism and racism. Figureheads of the suffrage movement – including Susan B. Anthony, Alice Paul, and Britain’s Emmeline Pankhurst – led mass protests, civil disobedience, and lobbying campaigns. These activists eventually secured the vote: for example, the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (1920) guaranteed American women the right to vote, and British women won partial suffrage in 1918 (full equal terms by 1928). The photograph below shows a 1913 American suffrage parade in Washington D.C., exemplifying this era’s mass mobilizations for women’s voting rights:

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Figure: Women marching in the Woman Suffrage Procession, Washington D.C. (1913). The banner reads “We demand an amendment to the Constitution of the United States enfranchising the women of this country.”

These first-wave feminists fought for formal equality under the law. Their agenda included access to education, legal rights in marriage and property, and equal pay. By winning basic political rights, first-wave campaigns established the idea that “women’s rights” were a legitimate political cause, creating new institutions (e.g. the National American Woman Suffrage Association) and networks of activists across states and nations.

Second Wave (1960s–1980s)

After a period of relative quiet following World War II, the second wave of feminism emerged in the 1960s and 1970s as a mass movement addressing both public and private inequalities. This wave built on first-wave legal gains and also took inspiration from civil rights activism. French existentialist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex (1949) was a foundational text: Beauvoir argued that women are not born, but “become” women through socialization, and she exposed how cultural norms treat women as “other” to men. In 1963 Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique galvanized American middle-class housewives by criticizing the suburban “cult of domesticity” and the frustration of educated women confined to homemaking. Friedan’s research – including surveys of Smith College alumnae – showed that many women felt unfulfilled by traditional roles. Her book ignited consciousness-raising groups and lobbying, captured the attention of politicians (President Kennedy established a Commission on the Status of Women), and became a best-seller. Within five years of Feminine Mystique, Congress passed the Equal Pay Act of 1963 and amended the Civil Rights Act (1964) to ban sex discrimination in employment.

Second-wave feminists also pursued broader social changes. They established rape crisis centers and shelters, challenged discriminatory workplace laws, and fought for reproductive rights (legal contraception and abortion). For example, in the United States the landmark Supreme Court case Roe v. Wade (1973) legalized abortion nationwide, a victory of the feminist movement for bodily autonomy (though this right has since faced political reversals). Activists like Gloria Steinem founded Ms. magazine (1971) and spoke publicly on feminist issues, while scholars like bell hooks (with Ain’t I a Woman, 1981) brought an intersectional perspective, highlighting how racism and classism shape women’s oppression. In Britain, the women’s liberation movement organized demonstrations (e.g. at the Miss World contest) and secured reforms in divorce and employment. In all these cases the slogan “the personal is political” underscored that private experiences of inequality – such as domestic abuse or restricted job opportunities – are rooted in public power structures. Second-wave feminism produced profound legal and cultural changes, reshaping expectations about gender roles.

Third Wave (1990s–2010s)

In the 1990s a third wave of feminism arose in the West, partly in reaction to perceived shortcomings of the second wave. Third-wave activists sought to build a more inclusive, pluralistic feminism. Key to this era was the development of intersectionality – a concept introduced by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989 – which analyzed how race, class, gender, sexuality and other identities intersect to produce overlapping oppressions. Crenshaw showed, for instance, that legal and policy discussions about discrimination often marginalize women of color, who face a “matrix of domination” beyond what single-axis analysis can capture. Influential third-wave theorists included Judith Butler, whose Gender Trouble (1990) argued that gender is not a fixed binary but a “performative” construct – something people do rather than something they are. Butler’s ideas drew on postmodern and poststructuralist thought, questioning essentialist categories of “woman.” The third wave also embraced queer theory and LGBT rights, as seen in groups like Queer Nation and scholars like Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. In practice, the 1990s saw movements like Riot Grrrl (feminist punk) and public reckonings such as the Anita Hill hearings (1991), when a young black woman’s testimony about sexual harassment in the Supreme Court confirmation process galvanized a new generation of women’s activism. Third-wave feminists emphasized sex-positivity, body diversity, and reclaiming derogatory labels. They critiqued earlier feminism for being too white or middle-class, leading to “feminisms” in the plural, including Black feminism (bell hooks, Patricia Hill Collins) and multiracial feminism. In summary, the third wave expanded the feminist agenda to include diversity, global consciousness, and the right to define one’s own identity.

Fourth Wave (2010s–Present)

Many scholars argue that a new fourth wave began around 2012. It is characterized by digital activism and a focus on combating sexual harassment, rape culture, and gender-based violence. Social media platforms became crucial organizing tools. For example, the #MeToo campaign (initially started by Tarana Burke in 2006 and gaining global prominence in 2017) allowed survivors of sexual assault to share their stories online, exposing abuse by powerful men across industries. The image below illustrates one landmark moment of this era: the 2017 Women’s March in Washington D.C., where millions of people protested for women’s and human rights the day after the U.S. presidential inauguration.

Figure: The Women’s March on Washington, D.C. (January 2017) – one of the largest single-day protests in U.S. history – exemplified the global mobilization of fourth-wave feminism Source: Britannica

Beyond high-profile protests, fourth-wave feminism centers issues such as online misogyny, body positivity (challenging media beauty standards), and the inclusion of transgender and nonbinary people in gender justice. Movements like #BlackLivesMatter have also been deeply influenced by feminist critiques of state violence. In academia and activism, there is growing attention to gender fluidity and deconstructing heteronormativity. In short, the fourth wave is marked by an intersectional, global consciousness aided by technology, continuing the feminist project with renewed emphasis on diversity, inclusivity, and rapid information-sharing.

Conceptualizing Feminism

Feminism can be understood in multiple dimensions: as an ideology, a theory, and a movement. Each perspective emphasizes different aspects of how gender inequality operates and how it can be changed.

As an Ideology

Feminism as an ideology is the belief system that underpins feminist goals. Central to this ideology is the critique of patriarchy – a social system where “women’s oppression through male domination” is normalized. Feminists argue that patriarchy permeates institutions and culture, from legal codes to family structures, entrenching male privilege. Feminist ideology also grapples with the distinction between equality (equal formal rights) and equity (addressing deep-rooted disparities). For example, achieving “equal pay for equal work” enshrines equality, but many feminists stress equity by advocating childcare policies or affirmative action to level the playing field for historically disadvantaged women. Broadly, feminist ideology asserts that social arrangements should be reconfigured so that gender does not determine one’s opportunities or value.

As a Theory

Feminist theory provides analytical tools to understand gender. A key insight (dating back to de Beauvoir) is that gender is a social construct rather than a simple biological essence. Feminist scholars examine how cultural norms “make” people into men and women, and how these norms justify power imbalances. Feminist theory also analyses power relations: for instance, how political and economic power is gendered, or how the personal sphere of family life is shaped by and reinforces public inequalities (the famous slogan “the personal is political” captures this idea). The public/private divide itself is a theoretical concern – feminism questions why unpaid domestic labor (the “private” sphere) is undervalued while paid work (the “public” sphere) is prized. In sum, feminist theory explores how meanings of gender are produced, and how they intersect with race, class, sexuality, and other structures of power.

As a Movement

Feminism as a social movement involves collective action and organizing. It is exemplified by grassroots activism (marches, protests, consciousness-raising groups), civil society organizations, and political lobbying. Historically, feminist movements have built broad coalitions – crossing racial, ethnic, and class lines – to effect change. For example, early feminist organizations in the West often aligned with labor unions, abolitionists, or civil rights groups to amplify their impact. Modern feminist movement-building includes international campaigns (e.g. UN Women’s HeForShe) and local NGO networks. Coalition-building is crucial: for instance, the international #MeToo phenomenon connected millions of women of all backgrounds in a shared cause. As a movement, feminism is both decentralized (comprised of many autonomous groups with sometimes differing goals) and transnational, reflecting a diversity of tactics from legal reform to street protest.

As a Theoretical Frameworks

Feminism also encompasses several core theoretical schools. (Liberal feminism) emerged with thinkers like Mary Wollstonecraft and Betty Friedan; it focuses on securing women’s equal rights through legal and political reform. Liberal feminists typically aim for formal equality (e.g. anti-discrimination laws, equal pay legislation). By contrast, (radical feminism) (Andrea Dworkin, Catharine MacKinnon) argues that patriarchy is so deeply woven into society that only a fundamental overhaul – sometimes a revolutionary change – can eliminate it. Radicals critique institutions (marriage, the state, sex, culture) as inherently patriarchal and often highlight issues like sexual violence and pornography as pillars of men’s power. (Marxist and socialist feminism) (Alexandra Kollontai, Silvia Federici) analyze how capitalism and private property intersect with patriarchy to exploit women’s labor (both paid and unpaid). Federici’s work, for example, ties the emergence of capitalism to the subjugation of women and the witch hunts of the early modern period. (Cultural or difference feminism) (Carol Gilligan, Luce Irigaray) emphasizes that men and women have different qualities – stereotypically valuing women’s caring or relational natures – and often argues for celebrating rather than erasing these differences. Meanwhile, (postmodern/poststructuralist feminism) (Judith Butler, Donna Haraway) deconstructs the notion of stable gender categories altogether. Butler’s Gender Trouble famously claims that gender is not an identity but an ongoing performance. Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto” (1985) uses the metaphor of a cyborg to break down binaries between human/technology and male/female.

Other frameworks include (psychoanalytic feminism) (e.g. Nancy Chodorow, Luce Irigaray), which draws on Freud and Lacan to explore unconscious gender dynamics, and (ecofeminism) (Vandana Shiva, Carolyn Merchant), which links the domination of women to the domination of nature. Ecofeminists point out that patriarchal attitudes toward the environment (exploitation, control) parallel those toward female bodies. Each of these frameworks provides different lenses to analyze women’s oppression – from state power to economic class to cultural symbols – and helps explain why sexism is so resilient.

Variants of Feminism

Feminism is pluralistic: within the broad movement and ideology, distinct “types” or schools of feminism emphasize different priorities or perspectives. These variants often overlap in goals but differ in theory or strategy. Key varieties include:

Liberal Feminism

Emphasizes legal equality and individual rights. Pioneers like Mary Wollstonecraft and Betty Friedan argued that women should have the same civil liberties, education, and job opportunities as men. Liberal feminists work within existing institutions (legislatures, courts) to secure gender parity through reforms – for example, pushing for laws on equal pay, non-discrimination, and suffrage. They tend to focus on removing formal barriers to women’s participation in public life, believing that women’s status will improve once legislation reflects true gender equality.

Radical Feminism

Argues that gender inequality is rooted in patriarchy itself, so mere legal equality is insufficient. Radical feminists like Andrea Dworkin and Catharine MacKinnon call for transforming or abolishing patriarchal institutions. For instance, radicals emphasize issues like sexual violence, bodily autonomy (e.g. fighting rape and trafficking), and criticize any tolerance of male privilege within culture and society. Unlike liberals, radicals may seek a reordering of family structures, sexuality norms, or even broader power hierarchies to eliminate male dominance.

Marxist/Socialist Feminism

Blends feminist and Marxist analysis to focus on class and economic exploitation. Thinkers like Alexandra Kollontai (Soviet era) and Silvia Federici argue that women’s oppression is tied to capitalism: women’s unpaid domestic labor and caregiving sustain the labor force, yet is undervalued. Socialist feminists advocate for socializing domestic work (state childcare, elder care services), equal work opportunities, and redistribution of resources. They often align with labor movements and critique the capitalist system alongside patriarchy.

Cultural (Difference) Feminism

Centers on celebrating differences between women and men. Cultural feminists suggest that women’s distinctive qualities (altruism, nurturance, emotional insight) should be valued and that society should integrate these traits. This strain sometimes overlaps with essentialism, the idea that male and female natures are fundamentally different. Cultural feminists aim to reclaim and honor “women’s culture” – for example, valuing mothers, community-building, art by women, etc.. Critics of cultural feminism argue it risks reinforcing stereotypes, but proponents see it as a critique of the male-centric ideal of success.

Black/Intersectional Feminism

Highlights the experiences of women who face multiple forms of oppression. Coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, intersectionality is central: Black, Latina, Asian, Indigenous, and other women of color note that race, class, and gender cannot be separated. Influential writers include Audre Lorde (Sister Outsider), bell hooks (Ain’t I a Woman?), and Angela Davis (Women, Race & Class). They pointed out, for example, that white feminism’s gains didn’t fully address racism, and that Black women’s liberation required confronting both sexism and racism simultaneously. Intersectional feminists work to include marginalized voices in the feminist movement, emphasizing collective struggle and solidarity across differences.

Postmodern/Queer Feminism

Influenced by poststructuralist thought, these approaches deny fixed gender identities altogether. Judith Butler argued that gender is a “performance” enacted through repeated behaviors, so categories like “man” and “woman” are not natural truths but social constructs. Queer feminism (often overlapping with gender studies) extends this by interrogating heteronormativity and binaries. Another key figure is Donna Haraway, whose 1985 “Cyborg Manifesto” imagined blurring boundaries between human/animal/machine and male/female. These perspectives open up possibilities for fluid gender expression and critique any essentialist view of womanhood or manhood.

Ecofeminism

Connects feminism with environmentalism. Ecofeminists argue that the domination of women and the domination of nature have common roots in patriarchal, capitalist societies. Activists and scholars like Vandana Shiva and Carolyn Merchant point out that practices harmful to ecosystems often parallel those harmful to women (pollution, resource extraction, body policing). For instance, indigenous women’s struggles over land rights or against dams are framed as both ecological and feminist issues. Ecofeminism promotes holistic and sustainable social structures, emphasizing care for the earth alongside care for people.

Each of these types of feminism represents an important stream within the wider movement, addressing particular issues or critiques. In practice, many individuals and organizations blend elements of different types: for example, an African feminist scholar might combine socialist and intersectional approaches to critique globalization’s impact on women in the Global South.

Feminism in Global Perspective

Feminism has often been critiqued as a Western import, and indeed different cultures have developed their own feminist traditions. Western feminism (e.g. in Europe and North America) has historically dominated public discourse, focusing on issues that concerned middle-class women (voting rights, workplace equality, reproductive choice). However, women outside the West have unique experiences shaped by colonialism, religion, ethnicity and local politics. For example, Islamic feminists (writers like Amina Wadud or Asma Barlas) advocate for gender equality within an Islamic framework, reinterpreting religious texts to support women’s rights. In India, Dalit feminism addresses both caste oppression and gender oppression: Dalit feminist scholars (like Bama or Gail Omvedt) argue that caste-blind feminism often ignores the compounded discrimination Dalit women face. Indigenous feminisms (among Native Americans, Australian Aboriginals, etc.) emphasize decolonization and reclaiming traditional roles and identities; they often challenge both patriarchal colonial authorities and patriarchal structures within their own communities.

African feminisms and Latin American feminisms likewise are rooted in local struggles. African feminists (e.g. the African Feminist Forum) highlight issues like colonial legacy, poverty, and gender-based violence, while Latin American feminists have long campaigned against military dictatorships and machismo culture. One influential movement is Mujeres Activas en Letras y Cambio Social in Chile, which led early feminist organizing in Latin America. Latin American feminists have also been vocal about reproductive rights and state violence (e.g. campaigns like Ni Una Menos against femicide in Argentina).

The concept of transnational feminism addresses these global connections and inequalities. It recognizes that globalization and capitalist markets affect women differently around the world. For instance, as Western countries recruit women into professional jobs, they may outsource domestic and care work to migrant women from poorer countries. Transnational feminist networks attempt to unite women across borders – sharing strategies, supporting labor rights for garment workers in Bangladesh, or advocating for refugees and migrants – understanding that “the links among patriarchies, colonialisms, racisms, and feminisms become more apparent” in a global context. Thus, contemporary global feminism emphasizes solidarity while respecting cultural differences, and works on issues like global reproductive justice (access to contraception and health care worldwide) and economic justice (challenging global capitalism’s exploitation of women’s labor).

Critiques of Feminism

- Internal critiques: Within feminism there have long been debates about who feminism serves and whose voices are heard. Early feminist waves were often criticized for centering only white, middle-class women. For example, second-wave feminism in the U.S. was largely shaped by white college-educated women. Black and ethnic minority women contested this focus. In 1981, bell hooks and others coined the term “white supremacist capitalist patriarchy” to describe how race, class, and gender interlock. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s intersectionality (1989) explicitly criticized feminism for ignoring how women of color experience oppression differently. Socialists and Marxists have also critiqued mainstream feminism for focusing on equality under capitalism without challenging economic exploitation. These internal critiques led to more nuanced movements – such as Black feminism, socialist feminism, and indigenous feminisms – which argue that a truly inclusive feminism must address race, class, colonialism and other hierarchies, not just gender.

- External critiques: Feminism faces pushback from various external quarters. Religious conservatives often view feminism as a challenge to traditional family and gender roles; in some countries, feminist activists are accused of threatening cultural or religious values. Critics also use cultural relativism to argue that feminist calls for women’s rights impose Western values on other societies. For example, when Western feminists condemn practices like female genital cutting or child marriage, some defenders invoke cultural relativism to dismiss external criticism. Additionally, an organized anti-feminist movement has arisen in recent decades (sometimes called the “manosphere” or “alt-right”) which portrays feminism as harmful to men and to social order. Some politicians and media personalities denounce feminism as radical or accuse feminists of being “man-haters.” These external attacks often create legal and social obstacles: for instance, movements for gender equality have been undermined by laws restricting discussion of LGBT rights or by campaigns characterizing feminist NGOs as “foreign agents.” Such backlash tends to galvanize feminists into resistance and solidarity (as seen in mass marches and digital campaigns).

- Common misconceptions: There are several misunderstandings about feminism that persist in popular discourse. One is that feminism is anti-men or inherently misandrist. In reality, mainstream feminist theory criticizes patriarchal power, not individual men as people. Feminists argue that dismantling patriarchy benefits everyone – men included – by freeing all genders from restrictive stereotypes. Another misconception is that feminism has “gone too far” or is no longer needed because women already have equal rights. This view ignores ongoing issues like gender pay gaps, underrepresentation in leadership, and violence against women. Conversely, some assume feminism is a single monolithic ideology; in fact, as shown, there are multiple feminist perspectives. Finally, some confuse feminism with extreme notions: for example, that feminists universally support all social changes (as if following a party line). In fact, feminism is diverse and debates abound (even feminists disagree on issues like sex work, transgender inclusion, or military policies). Clarifying these misconceptions is a continuing task of the movement: to explain that feminism’s core is equality and justice, not hatred or dogma.

Conclusion

Feminism is a complex and evolving force for social change. Across its history – from proto-feminist essays to suffrage marches, from women’s liberation rallies to online hashtags – the core theme has remained the quest for gender equality and human liberation. This chapter has traced feminism’s development through four waves of activism, its conceptual dimensions (as ideology, theory, and movement), and the myriad schools and variants that enrich its discourse. Key themes have included challenging the patriarchy, expanding legal rights, critiquing power and culture, and continuously broadening inclusivity. Future directions for feminism likely involve even deeper commitments to intersectionality and inclusivity. Issues such as climate change, global poverty, and technology’s impact on society present new arenas for feminist analysis (e.g. ecofeminism, cyber-feminism). Contemporary feminism must grapple with rapid social shifts – for instance, the gender implications of artificial intelligence – while insisting that voices of the most marginalized be heard. As feminist scholar Audre Lorde said, “there is no such thing as a single-issue struggle… we must all work together.” The future of feminism will therefore require coalitions across identities and borders, united by the belief that gender justice is a universal goal.

References

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. (1949).

- Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge (1990).

- Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. Routledge (1990).

- Davis, Angela. Women, Race, & Class. Vintage (1981).

- De Beauvoir, Simone. The Second Sex. Vintage (1953 English ed.).

- Dworkin, Andrea. Intercourse. Free Press (1987).

- Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. W. W. Norton (1963).

- Haraway, Donna. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. Routledge (1991).

- hooks, bell. Ain’t I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism. South End Press (1981).

- Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Crossing Press (1984).

- MacKinnon, Catharine. Toward a Feminist Theory of the State. Harvard Univ. Press (1989).

- Merchant, Carolyn. The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution. Harper & Row (1980).

- Mohanty, Chandra Talpade. “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses.” Feminist Review 30 (1988): 61–88.

- Pizan, Christine de. The Book of the City of Ladies. Penguin Classics (1989 English trans.).

- Truth, Sojourner. “Ain’t I a Woman?” Speech, Akron Women’s Convention (1851).

- Wollstonecraft, Mary. A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Penguin Classics (1975).

- World Health Organization. “Globalization and Women’s Health.” (1999). (Feminist organization report)