Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (1975) is a profound and transformative work that interrogates the evolution of punishment and the mechanisms of power in modern societies. Foucault, a French philosopher and historian, explores the transition from public spectacles of punishment in pre-modern times to the more insidious and pervasive systems of discipline that characterize the modern age. The book is not merely a historical account but a penetrating analysis of how power operates through institutions, bodies, and societal norms. By tracing the genealogy of punitive practices, Foucault unveils the subtle yet coercive forms of control embedded within modern disciplinary systems. His work challenges conventional understandings of justice and authority, shifting the focus from the legality of punishment to the ways in which power disciplines individuals and shapes societies.

In Discipline and Punish, Foucault begins with a stark juxtaposition: the brutal public execution of Damiens the regicide in 1757 versus the regimented daily routines of prisoners in 19th-century institutions. This contrast sets the stage for his central argument—that the nature of power has fundamentally changed. He argues that overt displays of sovereign power, such as executions and corporal punishment, have given way to more subtle, yet equally pervasive, forms of surveillance and normalization. This shift, he contends, is not simply a matter of humanizing punishment but a deeper transformation in the way power is exercised. Foucault describes modern discipline as a “political technology of the body,” where control is internalized by individuals through constant observation and subtle correction.

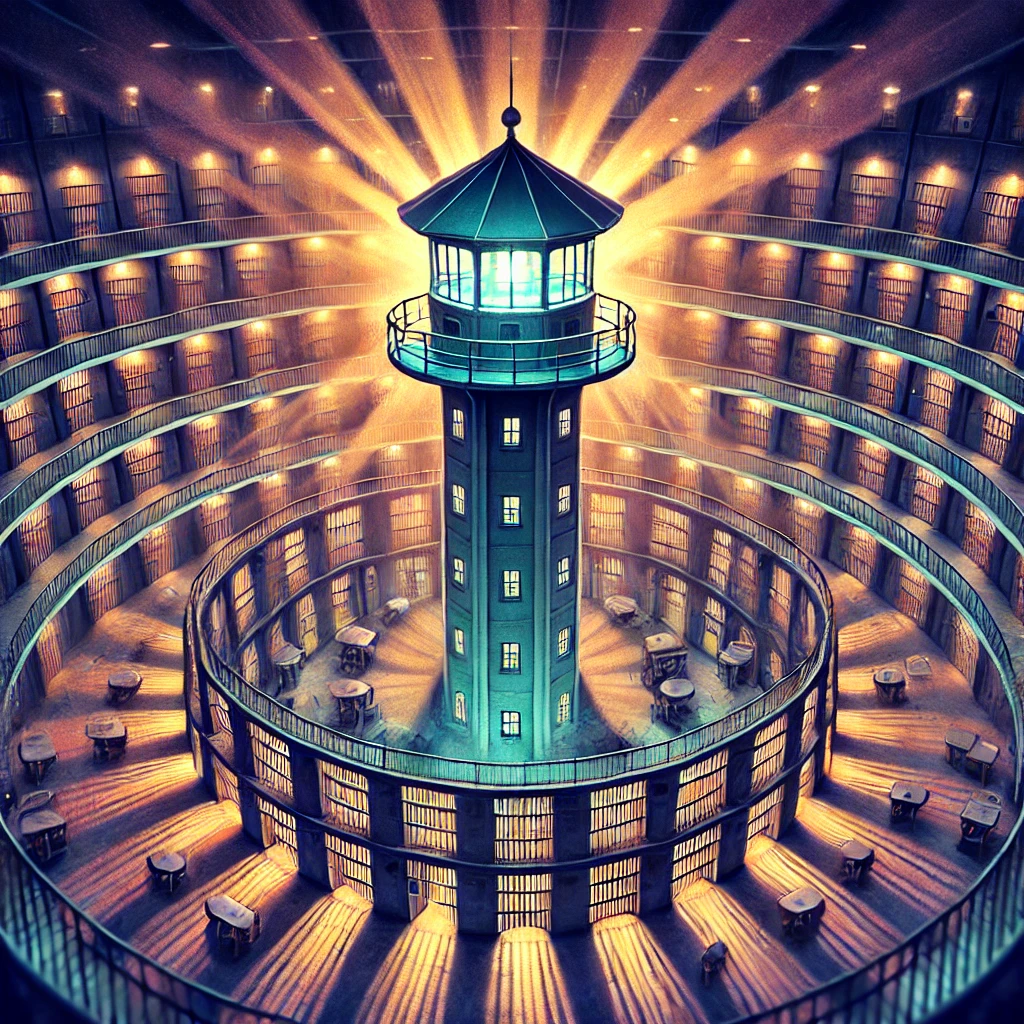

One of Foucault’s most influential concepts introduced in the book is the Panopticon, a theoretical prison design proposed by Jeremy Bentham. For Foucault, the Panopticon symbolizes the essence of modern disciplinary power. Its central watchtower, allowing a single guard to observe inmates without being seen, epitomizes a form of power that is invisible yet omnipresent. Foucault argues that this architecture of surveillance extends far beyond prisons to permeate schools, factories, hospitals, and other modern institutions. The Panopticon serves as a metaphor for how modern societies discipline their members by instilling a sense of being constantly watched, thereby encouraging self-regulation. As he succinctly puts it, “Visibility is a trap,” highlighting how surveillance transforms individuals into subjects who monitor and correct their own behavior.

Foucault’s work also delves into the historical conditions that made such disciplinary mechanisms possible, tying them to broader shifts in power and knowledge. He introduces the concept of “bio-power,” referring to the ways in which modern states regulate populations by controlling their bodies and behaviors. This regulation extends beyond punitive measures to encompass health, education, and productivity, illustrating how power operates through both repression and facilitation. Discipline and Punish thus serves as a crucial lens through which to examine the hidden workings of power in contemporary society. Its insights resonate not only in the study of history and philosophy but also in fields as diverse as sociology, political science, and cultural studies. Foucault’s exploration of power, discipline, and punishment invites readers to critically rethink the structures that govern their lives, making the work as relevant today as it was when first published.

Major Themes in Discipline and Punish

Power and Knowledge

The theme of knowledge and power is central in the work of Foucault. “Discipline and Punish” focuses on the reorganization of the power to punish, and the emergence of various fields of knowledge (sciences) that reinforce and interact with such power. The ‘power to punish’ is based on the supervision and organization of bodies in time and space, according to strict technical methods. The modern knowledge that Foucault describes is the knowledge that relates to human nature and behavior, which is measured against a norm. Foucault’s point is that one cannot exist without the other. The power and techniques of punishment depend on knowledge that creates and classifies individuals, and that knowledge derives its authority from certain relationships of power and domination.

The Body

The body as an object to be acted upon, but also as the subject of “political technology” is present throughout the work. Beginning with public execution, where the body is horrifically displayed, Foucault charts the transition to a situation where the body is no longer immediately affected. The body will always be affected by punishment—because we cannot imagine a non-corporal punishment—but in the modern system, Foucault says, the body is arranged, regulated and supervised rather than tortured. At the same time, the overall aim of the penal process becomes the reform of the soul, rather than the punishment of the body. Eventually, the concepts of the individual and the delinquent replace the reality of the body as the focus of attention, but the body of the criminal still plays a role. If anything can be seen as constant in this work, it is the idea that the body and punishment are closely linked.

The History of the Soul

Foucault’s project in Discipline and Punish is to account for the modern penal system, but he also presents a genealogical account of the modern soul. This is not only due to the fact that the soul gradually replaces the body as the focus of punishment and reform. It is also due to the fact that modern processes of discipline have essentially created that soul. Without the human sciences and the various mechanisms of observation and examination, the normal soul or mind would not exist. Ideas such as the psyche, conscience, and good behavior are effects created by a particular regime of power and knowledge. For Foucault, examining that regime is a way of looking deep into our souls. His history of the soul is also a powerful critique, because it makes us confront what we have become by excluding and marginalizing certain elements of our society.

The Prison and Society

The relationship between the prison and the wider society cannot be stressed enough. For Foucault, the prison is not a marginal building on the edge of a city, but is closely integrated into the city. The same “strategies” of power and knowledge operate in both locations, and the mechanisms of discipline that control the delinquent also control the citizen. Indeed, the methods of observation and control that Foucault describes originated in monasteries, in hospitals and in the army. Related to this point is Foucault’s argument that we cannot abolish the prison, because our ways of thinking about and carrying out punishment will not allow it. The prison is part of a “carceral network” that spreads throughout society, infiltrating and penetrating everywhere.

Paradox and Contrast

This is perhaps more a stylistic point than a theme, but Discipline and Punish reveals Foucault’s addiction to contrast and contradiction. From the shocking image at the beginning of the work to the many numbered lists and pairs of terms, the work is structured around a series of conceits and paradoxes. The idea that prison contains its own failure is a good example. Critics have criticized Foucault for what they see as his chronic obscurity, but at least part of the problem comes from his attitude to language and discourse. Discourses are complex structures in which people can become “trapped”: perhaps the experience of being trapped inside some of Foucault’s more difficult sentences is meant to echo this. Or perhaps, like many French philosophers, he was just fond of linguistic jokes.

References

- Haralambous and Holborn

- Explore more on Sociology